|

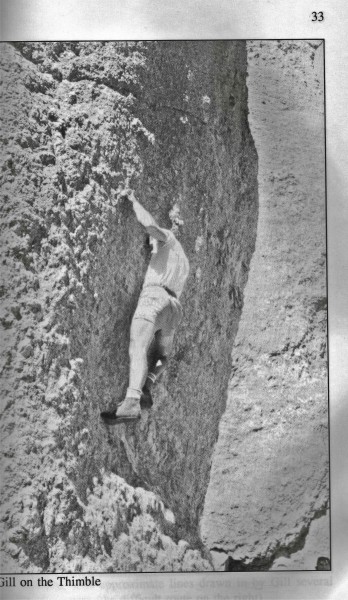

| John Gill on the Thimble, from Master of Rock |

But beyond the difficulty (after all Gill had bouldered V9 in 1959!), The Thimble represented the future of climbing. Whether runout on the granite knobs of the Bachar-Yerian (1981) or perched on the miniscule edges and pockets of To Bolt or Not to Be (1986), the climber is on terrain that was first definitively explored by Gill. Sustained steep face climbing, especially once the bolt wars had been resolved (more or less) has been the common currency of cutting-edge climbers world-wide.

Furthermore it marked a new era in terms of the scale and nature of the objective. None of Gill's more famous contemporaries would have viewed the Thimble route as a desirable objective, given the size of it and the blatant risk. Certainly none of them repeated it, nor is it likely they could have, given the specialized strengths of body and mind required for the route. But more interestingly none would really have seen the formation itself as much more than a footnote or afterthought, being too small in stature and too mundane in location to merit the effort and risk of an ascent, especially given that an ascent of El Cap probably posed less physical hazard.

This is where climbing went by the 1990s, to locations unheard of in the 60s or 70s, far way from the canonical sites of Yosemite or the Gunks to out-of-the-way spots such as Rifle or the Red River Gorge or a thousand areas in Europe, sharing in common the resource of steep featured rock. The pursuit of difficulty in climbing inexorably diminished the relevance of many of the big objectives in many people's eyes

The concentration of effort to free climb such a short objective, developed considerably already by Gill with his boulder problems, was a foreign concept in world climbing at the time. Perhaps it was his personality, reflected later in his mathematics career, patient, understated but deeply persistent in the pursuit of a solution to a problem that proved to be crucial. But prior to this ascent, the notion of a climber spending days working out a free-climbing challenge was unheard of. This obsessive quality is taken for granted now, like many of Gill's contributions to the modern sport of climbing, and its origin is for the most part forgotten.

We are all tempted to forget the place of history in the sport of climbing, to see it as lived in the present moment, in some edenic ahistorical state of mind or place. This is small-minded and ungenerous to the past. I try to imagine instead a young man, strong and determined, focusing his considerable powers of mind and body on this rock, listening to the wind whispering through the spires and pine forests of the Black Hills and making the decision, contrary to all expectation, in defiance of the norms of the time, to explore this undiscovered realm. This happened fifty years ago and utterly and irreversibly transformed the idea of climbing forever. Hopefully we can honor this achievement in our own memories and our pursuit of climbing.