|

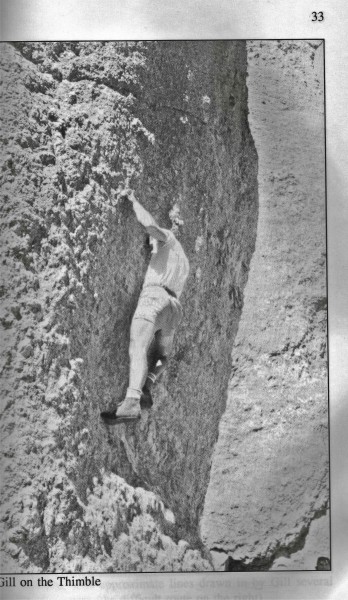

| John Gill on the Thimble, from Master of Rock |

But beyond the difficulty (after all Gill had bouldered V9 in 1959!), The Thimble represented the future of climbing. Whether runout on the granite knobs of the Bachar-Yerian (1981) or perched on the miniscule edges and pockets of To Bolt or Not to Be (1986), the climber is on terrain that was first definitively explored by Gill. Sustained steep face climbing, especially once the bolt wars had been resolved (more or less) has been the common currency of cutting-edge climbers world-wide.

Furthermore it marked a new era in terms of the scale and nature of the objective. None of Gill's more famous contemporaries would have viewed the Thimble route as a desirable objective, given the size of it and the blatant risk. Certainly none of them repeated it, nor is it likely they could have, given the specialized strengths of body and mind required for the route. But more interestingly none would really have seen the formation itself as much more than a footnote or afterthought, being too small in stature and too mundane in location to merit the effort and risk of an ascent, especially given that an ascent of El Cap probably posed less physical hazard.

This is where climbing went by the 1990s, to locations unheard of in the 60s or 70s, far way from the canonical sites of Yosemite or the Gunks to out-of-the-way spots such as Rifle or the Red River Gorge or a thousand areas in Europe, sharing in common the resource of steep featured rock. The pursuit of difficulty in climbing inexorably diminished the relevance of many of the big objectives in many people's eyes

The concentration of effort to free climb such a short objective, developed considerably already by Gill with his boulder problems, was a foreign concept in world climbing at the time. Perhaps it was his personality, reflected later in his mathematics career, patient, understated but deeply persistent in the pursuit of a solution to a problem that proved to be crucial. But prior to this ascent, the notion of a climber spending days working out a free-climbing challenge was unheard of. This obsessive quality is taken for granted now, like many of Gill's contributions to the modern sport of climbing, and its origin is for the most part forgotten.

We are all tempted to forget the place of history in the sport of climbing, to see it as lived in the present moment, in some edenic ahistorical state of mind or place. This is small-minded and ungenerous to the past. I try to imagine instead a young man, strong and determined, focusing his considerable powers of mind and body on this rock, listening to the wind whispering through the spires and pine forests of the Black Hills and making the decision, contrary to all expectation, in defiance of the norms of the time, to explore this undiscovered realm. This happened fifty years ago and utterly and irreversibly transformed the idea of climbing forever. Hopefully we can honor this achievement in our own memories and our pursuit of climbing.

5 comments:

While I appreciate the hagiographic salute, I think it's important to remember that it's a seemingly universal aspect of humanity to follow one's inspiration in sometimes a seemingly obsessive way.

My friends and I were inspired to try the ridiculous when young (and now!) before we ever heard of the exploits of other climbers (perhaps like the stories one hears of Native American kids spanking bears then running away madly, or stealing horses simply for the thrill of it).

What I most like about Gill is that he is able to talk about climbing in an intelligent artistic way.

The 50th anniversary of the FA of the Salathe Wall is this year as well. Somehow I doubt Robbins Frost and Pratt were worried about the landing on that one...

In response to the first anonymous comment, there is nothing hagiographical about the post, though if any climber merited such treatment it is probably Gill. Instead I am arguing for the profoundly historically important impact of this ascent, which was not done on the spur of the moment. The Thimble climb was a carefully calculated free climb of a sort that had simply never been done before.

While it may not be unheard of I wouldn't agree that it is a 'universal aspect of humanity to follow one's inspiration in sometimes a seemingly obsessive way.' Universal, as in everyone does it? I would say relatively few people do, but for me this is really not the key point.

For me the true wizardry of Gill lies in the way he truly freed himself of what he 'thought' he could do and just tried to do whatever he could. For me and many others the fact that others are doing something makes a huge difference in believing I can do it. Gill was able to transcend that for the most part and set a whole new standard. Not many humans do that in any field.

While he was not alone in this trait, it is precisely the way that Gill pursued his own limits with so little competition or co-conspirators that makes his achievements extraordinary to me. Of course his articulate and intelligent manner and fairly unique perspective on climbing are wonderful attributes as well.

I spent today alone in the Flatirons and along the way I was thinking about Jim Holloway and the way he, too pursued his own wild goals up there in isolation.

Cheers on the 50th anniversary, John!

I only had the privilege to go bouldering once with John Gill, about 25 years ago in Pueblo, not too long after his "re-discovery" by Bachar and Long. In person his low-key humility and humor reveal nothing of the drive and vision to invent a sport.

The entirely different climbing community today, that supports exploration, standards-pushing, etc. not only financially but socially and philosophically, creates a nurturing climate of behavior reinforcement (not always in a good way). Sponsorships and structured worldwide competitions give instant gratification and reward talent so young pros can train and travel full-time.

Gill literally created the sport in a vacuum - no one within 3 number grades of him, not once, but over and over, seemingly miraculously creating gardens of rock wherever he went, from southern Alabama and Illinois sandstone to Devil' Lake quartzite, Blacktail Butte limestone, and granite from Vedauwoo to Estes Park, the Tetons, and the Shawangunks, and penultimately Horsetooth and Pueblo, all incidental to his advancing professional education and math career! Most climbers likely wouldn't even think to look for Little Owl Canyon in its unlikely direction from town.

Try climbing anything technical in old RDs with their hard, slippery soles, then imagine being 30 feet up on shiny, sloping crystals, no spotter, pads, but a back-breaking log railing below.

My February trip to Pueblo with Neal Kaptain revealed the difference between getting up a problem, and doing it in Gill style. We toproped a technical double dyno that involved a body rotation and landing a sloper above a bulge that hit your chest and pushed you off unless you arched your back to clear it. Neal had recently done the double dyno on Flagstaff's Beer Barrel, but couldn't get within 18" of Gill's problem. Gill did it once, but wasn't satisfied until he repeated it with just 6" of swing at the moment of contact. He was already adding style points to things most would be happy to just send.

Post a Comment